Foreigner English ˈfȯr-ə-nər ˈiŋ-glish

n. When an English person mimics the accent or grammatical structure of another language to help them connect with its native speakers (or to hide the fact that they don’t know the language).

Case in point: footballer Joey Barton and manager Steve McLaren (yes, they are both English – not French and Dutch):

Listening to the recording of one of the interviews for my oral-history project, Guyana50.org, I heard myself asking the interviewee: ‘So yuh mudda would sell tings [at the market]?” The lady in question was struggling to understand me, so I subconsciously shifted my way of speaking in an attempt to make myself better understood.

It’s not the first time I’ve done it. After a while dating a guy from Spain, my good friend informed me that I appeared to be speaking “Foreigner English“. At the extreme, saying things like “We go shop?” – or just adding “no?” to the end of sentences. Ironically it was only when I went away to Brazil for a month and was speaking Portuguese most of the time that I regained my fluency in my mother tongue. I forgot all about Foreigner English and reverted to plain old English. When I got back, they were both amazed that I was so chatty. “You’re like a different person!”

Thinking about it now, I’d attribute this rediscovery of my own voice to the fact that in Brazil I was distinguishing between English and Portuguese, two very different languages – whereas at home it was between English and English-as-a-Spanish-language. My Foreigner English has come back in Guyana because once again the languages (Guyanese Creole and Standard English) have many words in common and so are harder to compartmentalise.

There is, I learned in an interesting seminar at the University of Guyana (UG) the other day, a sliding scale between the basiltect (the rural, ‘deep’ version of Guyanese Creolese) and the acrolect (the urban, version of Creolese – more aligned to Standard English).

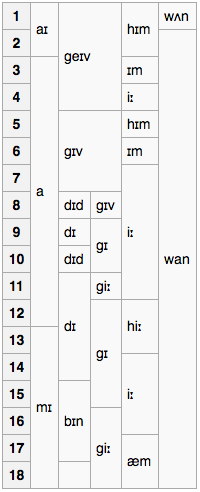

Some researchers have even mapped this scale. Below is the phrase ‘I gave him one‘ (UK readers, please get your minds out of the gutter) rendered in 18 different variations (from Bell 1976, via Wikipedia). I don’t really understand phonetic spelling but it’s pretty interesting.

Anyhow, point is, instead of switching between two distinct languages, people move across the scale depending on who they’re talking to and where. So when people in Guyana are talking to me, someone from England, they will move as close as they can to the acrolect. For some people this is no problem at all – perhaps those who grew up in a Standard English-speaking home or who have studied overseas. For others it’s unnatural and something they have to do consciously, even with serious concentration.

The other day, I heard a Guyanese academic recounting the difficulties of making small talk in England. The effort to not speak Creolese made the conversation feel unnatural. Another friend recently spoke apologetically of “mixing up my Creolese” when speaking to me. Even the President, before giving his speech at a press conference the other day, apologised in advance for his pedantic language: “I learned that medium is singular and media is plural, so excuse me when I say ‘The media are’ rather than ‘the media is’.” (I paraphrase, didn’t note his exact words). Was he trying to show off his grasp of the intricacies of Standard English or pre-emptively quash any sense that he’s being a linguistic snob and grammar Nazi?

As far as I know, Guyanese people don’t expect English visitors to speak Creole, because we both speak ‘English’ right? So why does the Guyanese speaker not understand everything the English speaker says, and visa versa? Because they’re not necessarily both speaking Standard English – the Guyanese person may actually be speaking Creolese.

Guyana, we’re told, is an English-speaking country – the only one on the continent. Yet, depending on their social or family background, someone in Guyana may easily have grown up speaking only Creolese at home, with friends and even in the classroom. They may rarely have heard or engaged in speaking Standard English while growing up (beyond films, music etc). Yet they’re expected to suddenly talk Standard English when they meet a speaker of that language, and to the same proficiency? I’ve been speaking Standard English my whole life, but who expects me to suddenly speak Creole on entering the country?

I’d like to be able to. Put me in the middle of a conversation with two people speaking Creolese and I won’t understand everything. Sometimes anything. So I’m missing out on a huge part of the Guyanese experience and conversation. It’s a definite loss, both for me and for the Guyanese people who don’t speak Creolese either (they exist). Because the language seems so expressive and lively.

So for now, until I am more familiar with Creolese, I find myself trying to make myself understood in certain situations by changing my accent slightly, adopting new Guyanese words like ‘gaff’ (a great word meaning to chat, gossip, catch jokes with someone) or ‘high’ (instead of drunk), and sometimes shifting the order of my words. My sisters have also noticed Guyanese noises of assent and agreement creeping in my voice when I speak on the phone. I say ‘morning’ with an exaggerated ‘r’. When I call out a bus stop, I try to change how I speak to sound less conspicuous. “NEXT CORNER!” I shout. I tried it out on some friends. “You sound Jamaican” they chuckled. Goodness knows what the other passengers think. I imagine them collapsing into fits of laughter the minute the minibus drives off. Should I stop trying to meet people halfway? Is it more authentic to speak in your own voice or in a way that people around you understand?

When you hear someone changing their way of speaking to match another’s, I have to admit it comes across as a bit patronising. But I think chameleoning (I’ve just make that up) and switching between languages shows sensitivity. You just have to be careful to distinguish between the different languages you’re using, or you could end up losing or colouring your natural speech or mother tongue.

At the same UG seminar, one participant reflected on hearing a teacher in Jamaica switch between Jamaican Creole and Standard English. “It was beautiful to see,” he said, several times, in awe of the woman’s ability to seemlessly slide between the languages as the occasion or situation demanded.

I think that’s a pretty good goal. Who wants to see Creolese die out and be replaced by Standard English alone? Maybe some Guyanese do. But I don’t think you have to kill one to preserve and elevate the other. No?

[Featured image: Roland Tanglao, via Flickr/Creative Commons]